Hey, Friend,

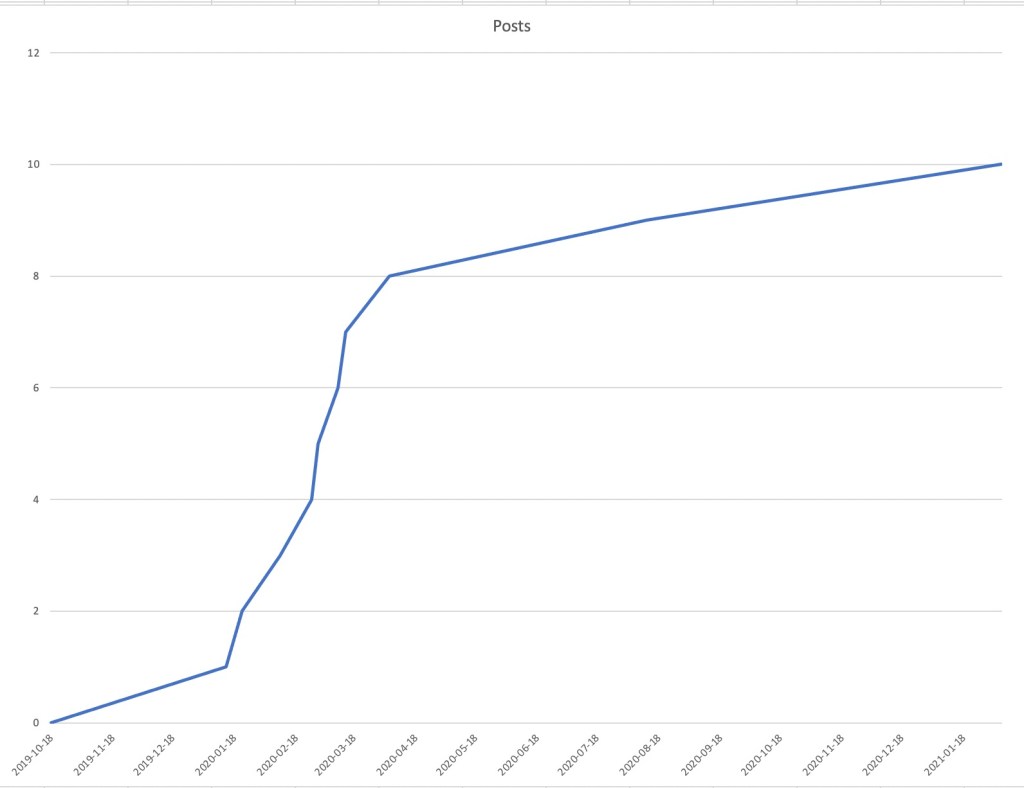

It was a year ago that I wrote about things online. Making reference to COVID in this and some other posts and reflecting on the complexity of change. A year ago!

Online learning has been on my mind ever since 2001, when I was asked to lead a group of people who would develop the first online language courses at the University of Waterloo in Canada. And when reading the newspaper — online during the week and with real paper and great pleasure on weekend — or when listening to friends and colleagues, these last twelve months I have not been the only one thinking about online learning. So what’s up?

Kids are protesting to be allowed to return to their classrooms, parents want to reclaim the work and study spaces in their home, and some piece and quiet, university students are suing their alma mater, claiming that tuition for online courses should be lower, and psychologists and pedagogues warn that the (learning) achievement gap is widening because of inferior online instruction. Looks like a bleak picture is emerging in the puzzle of the pandemic.

These worries and concerns have been real for many people, and they are understandable. People have been worried about and frustrated with new technologies at least since the industrial revolution in the western world. Think of the Luddites. Yet research on online learning has shown that relying on this modality is surely not all bad. Doesn’t this warrant a closer look?

We thought so a few years ago and looked back on how students had been doing in our online courses in the ten years between 2003 and 2013 (If you’d like to read the full article…). What did we learn from this study?

- Positive:

- Online learning provides access to more students or participants, because they avoid scheduling conflicts (especially for asynchronous modalities) and geographical distance is not a barrier anymore.

- Students can and in their majority do achieve learning outcomes that are very similar the the ones of their peers in comparable classrooms.

- Online courses can present more learning material (than in classroom teaching) from which students can choose, facilitating individualization.

- Students who took a balanced mix of online and classroom courses achieved higher grades in the program.

- Negative:

- Students have a strong preference for classroom socialization (perhaps especially so for language classes at a university, but that’s a different topic).

- Students miss the in-person interaction with the instructor and perceive teacher feedback as lagging.

- Students find online courses to be more work-intensive.

So, in many ways, online learning is not remote at all. In some of the next posts, I will take a closer look at the individual points — both positive and negative — to see what we can do with quality of online learning. It is here to stay even with herd immunity. It has come a long way in the last twenty years or so. And most important of all, in my opinion, it has changed distance education beyond recognition. So, not remote at all.

You will find other posts on RoLL — On Research on Language and Learning — under this category of posts on the Panta Rhei blog.