The 70 years of AI (see McCarthy et al. (1955)) have seen an intertwining of language and computing. At first, computers, as the name says, were meant for computation, for the fast calculation of a few complex equations or many simple ones. It was later that calculations were done with texts as input. Famously, first successful computations of and with letters were done at the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park to break the German Enigma cipher as part of the British effort in World War II. After the mathematician Alan Turing and his colleagues deciphered messages by the German Luftwaffe and navy successfully, he proposed that these new machines could also be used for language (Turing (1948) quoted in Hutchins, 1986, pp. 26-27). The Turing test (Turing, 1950) stipulated that a calculating machine, a computer, could show intelligence if a human interlocutor on one side of a screen could not tell whether they had a conversation with another human or a machine on the other side of the screen. ChatGPT passed this test successfully in 2024 (Jones & Bergen, 2024).

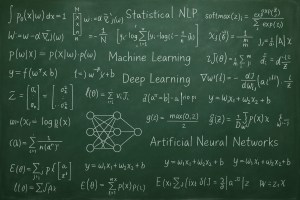

With the beginning of the Cold War, machine translation seemed to hold a lot of promise. Researchers’ predictions of success were based – at least in part – on the idea that translating from Russian into English is just like deciphering an encrypted message; letters have to be exchanged for other letters according to certain patterns in a deterministic mathematical process. Of course, this did not do justice to the complexities of language, communication, and translation. So, the then nascent field of natural language processing (NLP) turned to grammatical rules of formal (mathematical) grammar and items, the words in electronic dictionaries. The computer would “understand” a text by parsing it phrase by phrase to build an information structure similar to a syntactic tree, using grammatical rules. Such rules and the list of items with their linguistic features had to be hand-crafted. Therefore, the coverage of most NLP systems was limited. In the 1990s, researchers began to move away from symbolic NLP, which used linguistic symbols and rules and applied set theory, a form of mathematical logic, on to statistical NLP. Statistical NLP meant that language patterns were captured with calculating probabilities. The probability of one word (form) following some others is calculated for each word in a large principled collection of texts, which is called a corpus. In the 1990s and 2000s more and more corpora in more and more languages became available.

This is part of a draft of an article I wrote with Phil Hubbard. In this paper, we are proposing a way in which teachers can organize their own professional development (PD) in the context of the rapid expansion of Generative AI.

We call this PD sustained integrated PD (GenAI-SIPD). Sustained because it is continuous and respectful of the other responsibilities and commitments teachers have; integrated because the PD activities are an integral part of what teachers do anyway; the teacher retains control of the PD process.

The full article is available as open access:

Hubbard, Philip and Mathias Schulze (2025) AI and the future of language teaching – Motivating sustained integrated professional development (SIPD). International Journal of Computer Assisted Language Learning and Teaching 15.1., 1–17. DOI:10.4018/IJCALLT.378304 https://www.igi-global.com/gateway/article/full-text-html/378304

In the 1990s, progress in capturing such probabilities was made because of the use of machine learning. Corpora could be used for machines to “learn” what the probability of certain word sequences is. This machine learning is based on statistics and mathematical optimization. In NLP, the probability of the next word in a text is calculated, and in training, that result is compared to the word that actually occurred in the text next. In case of an error, the equation used gets tweaked and the calculation process starts anew. The sequences of words are called n-grams.

The resulting n-gram models were replaced in the mid-2010s with artificial neural networks, resulting in the first generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) – GPT-1 – in 2018. This marks the beginning of GenAI as we know it today. GPTs are large language models (LLMs) from OpenAI. Today, an LLM is pre-trained using deep learning, which is a more complex subset of machine learning. The pre-training means that when processing the text prompt, each artificial neuron in the network of the LLM receives input from multiple neurons in the previous layer and carries out calculations and passes the result to neurons in the next layer. GPT-4, for example, processes text in 120 layers. The first layer converts the input words, or tokens, into vectors with 12,288 dimensions. The number in each of the 12,288 dimensions encodes syntactic, semantic, or contextual information. Through these calculations, the model provides a finer and finer linguistic analysis at each subsequent layer.

The enormous number of calculations – an estimated 7.5 million calculations for a sentence with five words – results in plausible text output and consumes a lot of electric power. The latter is the main cause for the environmental impact of GenAI. The former is the main factor in the attractiveness of GenAI not only in language education but also in industry and increasingly in society at large.

References

Hutchins, J. (1986). Machine translation: Past, present, and future. Ellis Horwood.

Jones, C. R., & Bergen, B. K. (2024). Does GPT-4 pass the Turing test? arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.20216

McCarthy, J., Minsky, M. L., Rochester, N., & Shannon, C. E. (1955). A proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. http://www-formal.stanford.edu/jmc/history/dartmouth/dartmouth.html

Turing, A. M. (1948). Intelligent Machinery (Report for the National Physical Laboratory). Reprinted in D. C. Ince (Ed.), Mechanical Intelligence: Collected Works of A. M. Turing (pp. 107–127). Amsterdam: North‐Holland.

Turing, A. M. (1950). Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind, 59(236), 433–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433

Discover more from Panta Rhei Enterprise

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Silicon learns our tongues, from ciphers to chatty ghosts,power hums, words bloom. Rules once hand-carved tight,now probabilities breathe wide;corpora become. Teachers steer the craft:sustained, with integrated practice: slow fire, steady light, onward…

https://parenting-support.net/ https://youtu.be/iGL9Y2tTr5o?si=DhsGCb4PIkFGTmiW Confidentiality Notice: This transmission (and/or the attached documents) may contain confidential information belonging to the sender, which is intended solely for the named recipient. Content is copyrighted. If you are not the named recipient, you are hereby notified that any unauthorized use, disclosure, duplication and/or distribution of the following contents is strictly prohibited. If you have received this transmission in error, please notify us immediately. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person